М. В. Ломоносова Филологический факультет Кафедра английского языкознания Когезия и когеренция в философском дискурсе на материале эссе Бертрана Расселла "О природе знакомства". Курсовая

Скачать 1 Mb. Скачать 1 Mb.

|

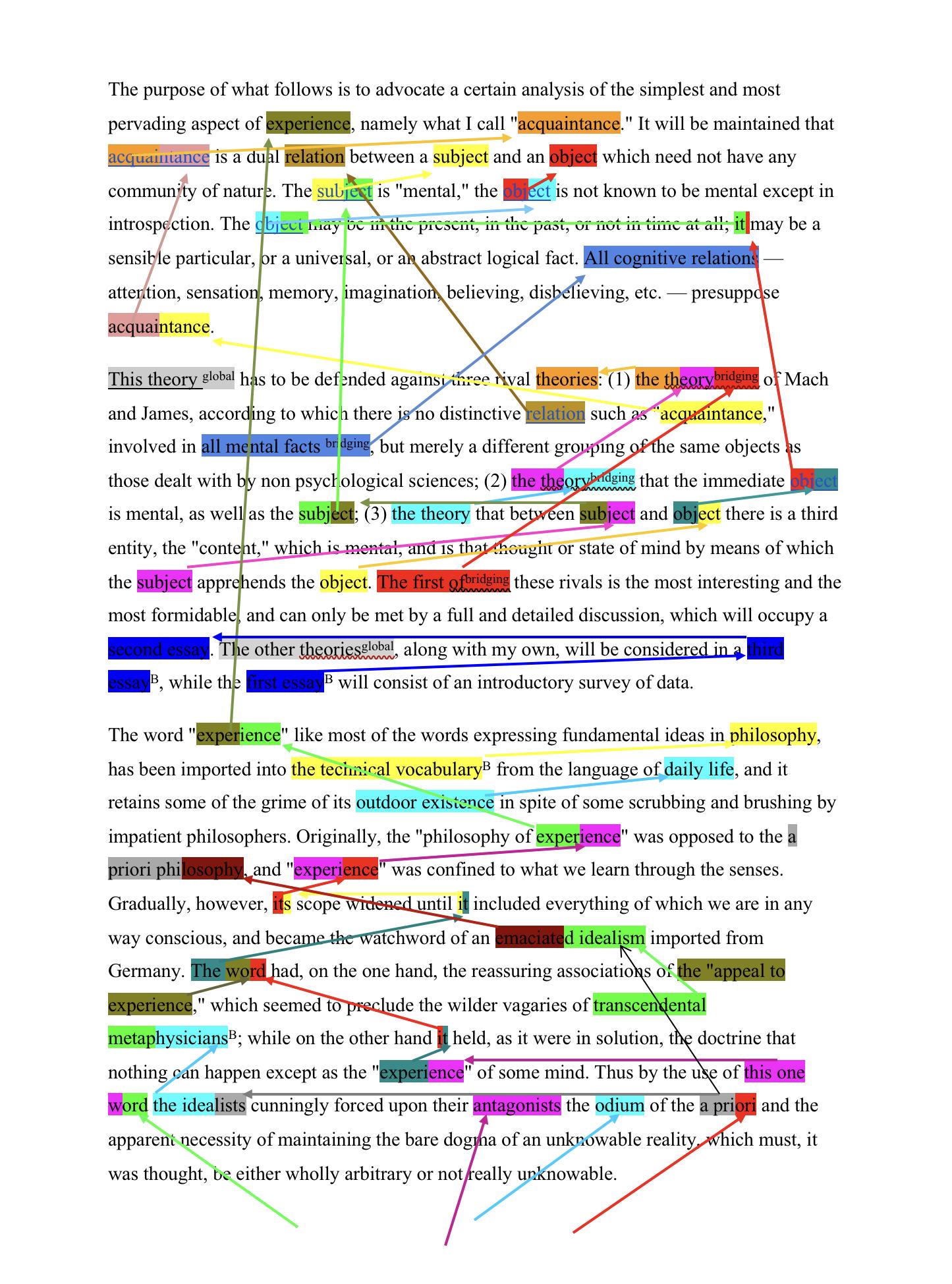

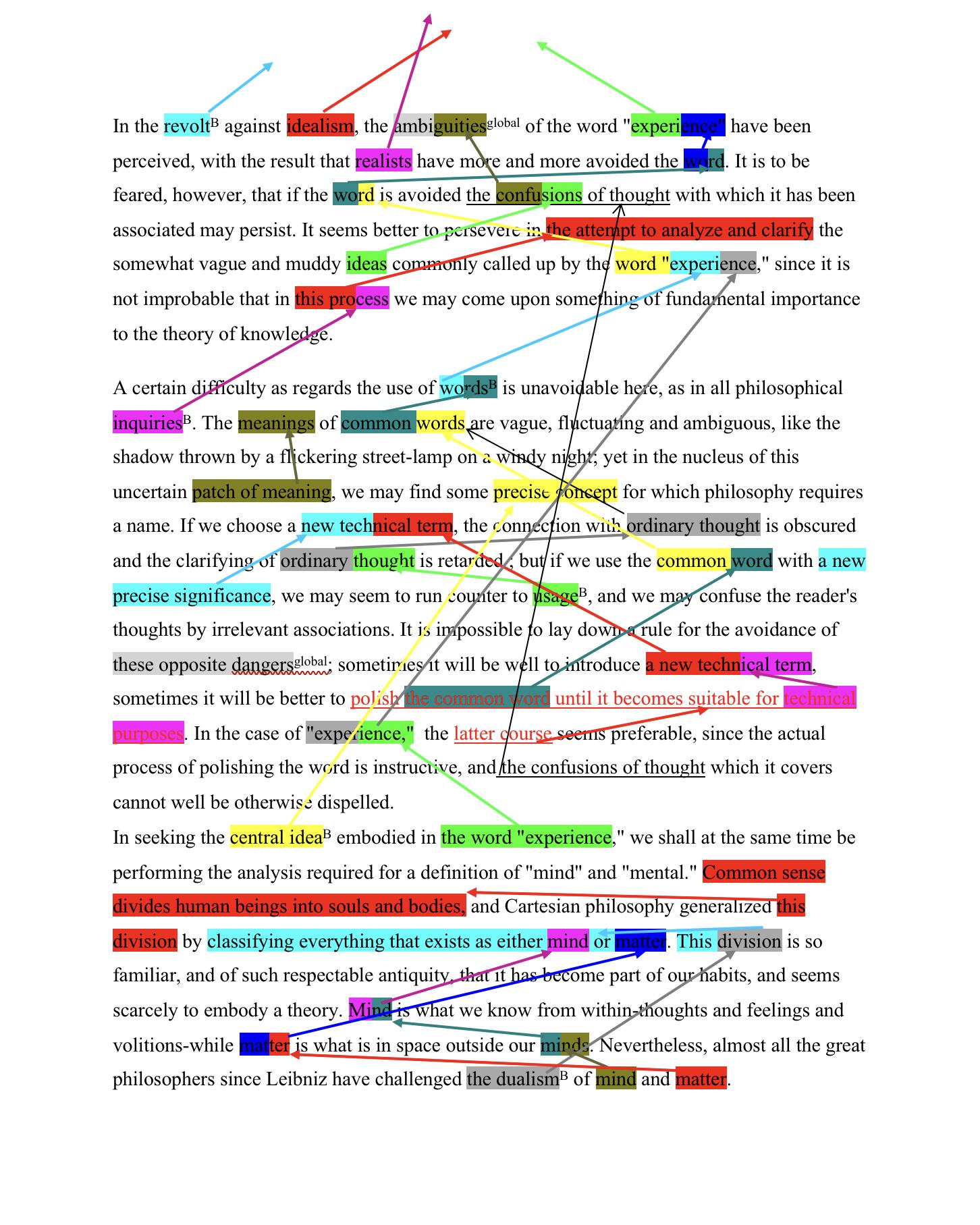

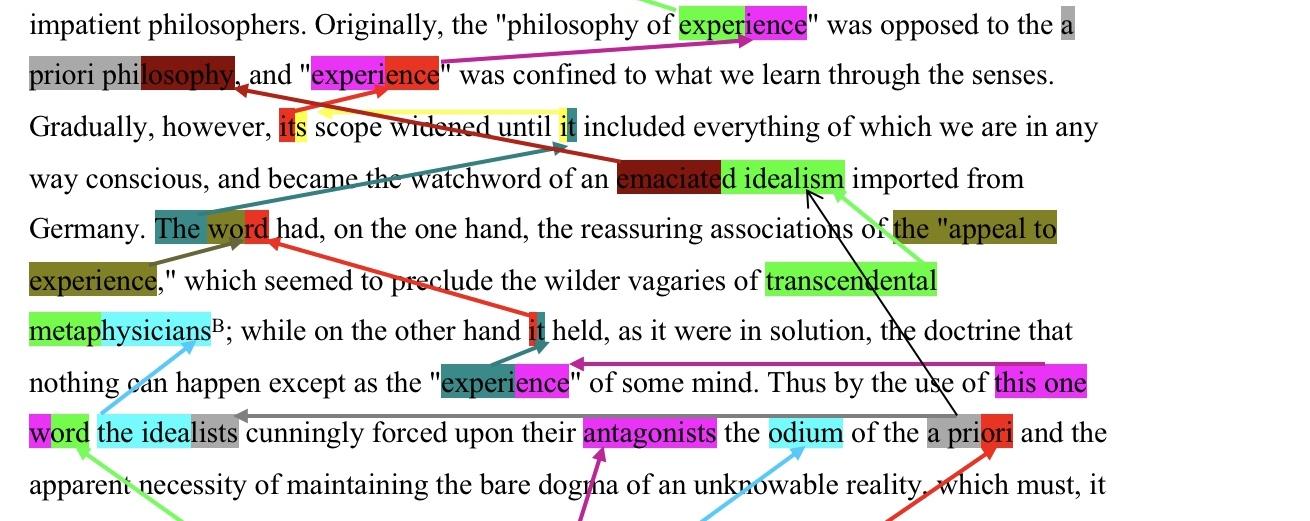

Verbal ellipsis.By verbal ellipsis we mean ellipsis within a verbal group (in alternative terminology, also verbal (verb) phrase; however, there is ambiguity in its usage see Rodriguez-Navarro; for a similar definition featuring the term verb phrase see Murguia 2004; she, however, divides elliptic verb phrases into three groups: verb phrase ellipsis, gapping and pseudogapping; for other classifications see Craenenbroeck and Temmerman 2019). Lexical ellipsis.Lexical ellipsis occurs every time when the lexical verb in a verbal group is omitted (Halliday and Hasan 1976), for example: Is John going to come?- He might. He was to, but he may not. - He should, if he wants his name to be considered. Here the auxiliary part of the group being its head (which is not typical for it) indicates that the main part is missing (ilid. p. 170). Operator ellipsis.Operator ellipsis (for a definition of operator within a verbal group see Halliday and Matthiessen 2004) occurs every time when the auxiliary part is omitted (whereas typically it should be found there), for instance: Has she been crying? — No, laughing. (ilid. p. 175). Clausal ellipsis.Clausal ellipsis occurs every time when in addition to the verbal group its complements are omitted (ilid. p. 197): Who taught you to spell? — Grandfather did. (taught me to spell is presupposed) Has the weather been cold? — Yes, it has. (been cold is presupposed) Clausal ellipsis is based on the distinction between modal and propositional elements which is characteristic of “statement, question, response etc clauses in English” which in combination form a two-part structure (this opposition appears to correspond with noun group versus verb group in generative grammar, see Murguia 2004): The Duke was | going to plant a row of poplars in the park. (rf. Halliday and Hasan 1976 p. 197) By this we can account for the fact that no singular elements can of a verbal group can be missed. Only the modal or propositional element taken as an indecomposable unit can be omitted. Cohesion and coherence analysis as a means of interpreting philosophical texts.The study of deep, implicit meanings contained in texts of philosophical discourse is one of the most controversial and problematic issues of modern hermeneutics. Any interpretation implies the possibility of an arbitrary explanation of the text, and the less objective the means with which the researcher begins to interpret the text are, the more arbitrary the result of such a study is. When getting to know philosophical texts, taking into account their multimodular, terminologically complex structure, these are not the meanings of individual words that acquire a muddy and unclear character, but rather the relations between them, not “bundles” of semantic meanings, but with what threads and how these bundles are connected (Malevinsky 2017). When we are faced with the need for a correct and accurate interpretation of these relationships, it is important not to make a mistake in choosing an approach to the analysis, as together they form a clear structure of axonomorphic references that signal one precise and not another understanding of the text. A certain non-linguistic, cognitive-psychological aspect of interpretation manifests itself in them, which is one of the key sides of hermeneutics as a philosophical and philological theory of interpretation. “To understand an author better than he understood himself” was the main goal of hermeneutical analysis according to Friedrich Schleiermacher (Schleiermacher 1998). Revealing this aspect of the so-called “hermeneutical circle” is provided by the analysis of hidden semantic connections in the text. By these connections and references, one should understand the sources of essential semantic relations within text — cohesion and coherence, which were described in detail in the previous chapters of the present paper and are considered in the analysis mainly from a cognitive point of view, that is, from the point of view of how these structural relations in the text affect its perception by the reader. The analysis is based on an excerpt from the early essay of the eminent British philosopher of the 20th century, Bertrand Russell, “On the Nature of Acquaintance” (cited from Russell 1914). The analysis aims to identify all cohesion bonds that are visually indicated by arrows (which is a common practice: see, for example, Yang 1989). The colors of the arrows and related elements do not have any relevance and are introduced for clarity. If any element in the text is both a source and a recipient of cohesive relation, then it is marked by two colors, the first part highlighting the “outgoing” relationship and the second — the “incoming”. In cases of associative anaphora (bridging relations), the source element is marked in the superscript “B” (or “bridging”), in cases of global reference (extended reference in terms of Halliday and Hasan 1976), the source element is marked in the superscript “global” (Fig. 1 , 2).   In this passage of the essay, cohesive and associative connections clearly cross the boundaries of entire paragraphs, consistently building an almost “visual” picture of meanings. Describing such an essential part of the theory of knowledge as “acquaintance” and alternative theories to it, Russell establishes references (intentionally or unconsciously) that cross the boundaries of entire paragraphs and form a pronounced tree structure, the “trunk” of which is the definition of “acquaintance”. The most important feature of this structure is that with its help B. Russell establishes the linear-temporal perception of the concept by the reader. The first bundle of connections - references related to Mach’s alternative theory - is referred to the first part of the definition ("acquaintance is a dual relation between..."). A number of connections based on the description of the second theory refers to the second part of the definition (the one which specifies the nature of the relationship between the subject and the object). Finally, the third bundle, referring to the same part as the second, introduces only an additional component into the relation between the subject and the object. Thus, an appeal to cohesive ties shows why the first alternative theory is “the most interesting and most formidable”: it denies the very fact that such a relation as acquaintance exists, while others relate only to its aspects and nuances, without overturning the general rule. This “skeleton” of the rhetorical structure is “built” of referential references, less often on bridging connections. Grammatical cohesion (in contrast to lexical) does not participate in its formation and remains confined within the framework of individual phrases, without contributing to the general coherence of the text. The very first reference of the next paragraph signals that the review of philosophical theories of cognition is completed, and returns to the main topic of the essay - the reveling of the concept around the central notion — “experience” (stated in the definition). As the philosopher’s intention changes, the cohesive means that he resorts to also change in the text: not only lexical, but also grammatical reference becomes more frequent and significant, more often in neighboring sentences. Crossed and interwoven cohesive chains (together with the associated bridging relations: a priori philosophy - emaciated idealism - transcendental metaphysicians - the idealists - a priori; experience - it - its - experience - experience - its - it - the word - it - experience - this one word) reflect the idea of contradiction and confrontation between the approaches of realists and idealists.  Since Russell himself is an inspiration for the “revolt” against idealists (Copleston 1975), he emphasizes the ambiguous use of the term by proponents of a priori philosophy. This contradiction is based on intersecting anaphoric ties (we mark them as cohesive chain 1 and 2): the word (1), the “appeal to experience” (1), transcendental metaphysicians (2), it (1), experience (1). At the same time, the last two elements of these are included in the phrase, which is the basic axiom of a priori doctrine of experience. Thus, the same reference chains participate in opposing statements from the point of view of different philosophical movements, by which the author demonstrates a clear instance of terminological manipulation. Comparing these features with those considered earlier, we can conclude that the movement of meaning in Russell's text is unstable, dialectical. This is reflected in the connections within the work, or rather, is formed by them. The rhetorical structure of the first four paragraphs of the essay goes back to the basic types of rhetorical structure: parallel and linear presentation of information. Parallel structures, by definition, mean that ideas that are similar in content or function are expressed in a similar way (Strunk 2011). They allow B. Russell to clearly distinguish between the existing approaches to the theory of knowledge in philosophy, showing “how the ideas are linked, rather than forcing the reader to work to see the connections” (Watling 2015). In turn, the linear, “leaning to the left” tree of the rhetorical structure (Mann, Thompson 1987) and the sequential attachment of theme-rheumatic complexes to each other also brings to the style in which Russell reveals the meaning of the term “experience” a shade of pseudo-narrativity. Cohesive bonds are no longer built with regard for how the reader perceives them linearly, but how the events presented by the author occurred one after another in time. In such chains of conclusions, grammatical cohesion plays its inevitable role, as it occurs in the reflection (similar to the previous one) on the need to use “general words” or “new technical terms” in relation to the fundamental concepts of the theory of knowledge. In general, the same remarks apply to it, with the exception that these are the concepts of “common word” and “new technical term” (together with their coreferents and elements connected by bridging connections) that make up an antagonistic pair of cohesive chains here. There are two links that are particularly important and lead from the first phrase of a new paragraph (the central ideaB ⇒ a precise concept in the nucleus of meaning and the word “experience” (through the intermediate link “experience” at the end of the previous paragraph) ⇒ the word experience) and marking the completion of that introductory substantiating which was presented immediately before. The picture is changing again, and some references (in our case most often - reiteration) build a parallel rhetorical structure of paragraph division, while others lead reader's thoughts within the paragraphs. The text is based on a pronounced tendency to form a structure similar to the one of natural classification: the central concept becomes a recipient of cohesive bonds, but not their source (Lakoff 1987; Krikmann 1998). Furthermore, peripheral concepts and aspects of the basic concept are grouped around it via lexical cohesion, or its history of existence in philosophical discourse is structured using the so-called “cohesive chain” (see 6.1.3 and Halliday and Hasan 1976). Thus, a strict distinction between the concepts of scientific and terminological tools in the text by Bertrand Russell and their consideration in retrospection of development are fully reflected in cohesion and local coherence of the text: the author verbally “visualizes” his concept in the text, turns it into a kind of graph of cohesive ties, which tends to be close to linear or tree-like structures. Understanding these connections is crucial for understanding the text in general. |