И. В. Арнольд

Скачать 1.82 Mb. Скачать 1.82 Mb.

|

|

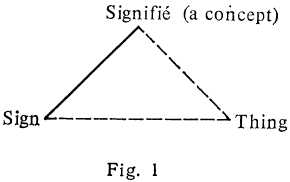

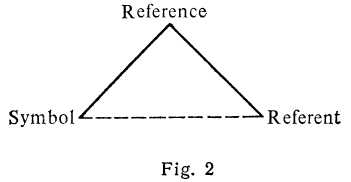

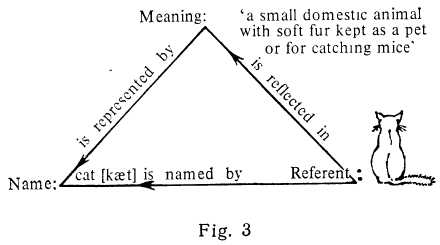

§ 1.6 THE THEORY OF OPPOSITIONS This course of English lexicology falls into two main parts: the treatment of the English word as a structure and the treatment of English vocabulary as a system. The aim of the present book is to show this system of interdependent elements with specific peculiarities of its own, different from other lexical systems; to show the morphological and semantic patterns according to which the elements of this system are built, to point out the distinctive features with which the main oppositions, i.e. semantically and functionally relevant partial differences between partially similar elements of the vocabulary, can be systematised, and to try and explain how these vocabulary patterns are conditioned by the structure of the language. The theory of oppositions is the task to which we address ourselves in this paragraph. Lexical opposition is the basis of lexical research and description. Lexicological theory and lexicological description cannot progress independently. They are brought together in the same general technique of analysis, one of the cornerstones of which is N.S. Trubetzkoy’s theory of oppositions. First used in phonology, the theory proved fruitful for other branches of linguistics as well. Modern linguistics views the language system as consisting of several subsystems all based on oppositions, differences, samenesses and positional values. A lexical opposition is defined as a semantically relevant relationship of partial difference between two partially similar words. Each of the tens of thousands of lexical units constituting the vocabulary possesses a certain number of characteristic features variously combined and making each separate word into a special sign different from all other words. We use the term lexical distinctive feature for features capable of distinguishing a word in morphological form or meaning from an otherwise similar word or variant. Distinctive features and oppositions take different specific manifestations on 25 different linguistic levels: in phonology, morphology, lexicology. We deal with lexical distinctive features and lexical oppositions. Thus, in the opposition doubt : : doubtful the distinctive features are morphological: doubt is a root word and a noun, doubtful is a derived adjective. The features that the two contrasted words possess in common form the basis of a lexical opposition. The basis in the opposition doubt :: doubtful is the common root -doubt-. The basis of the opposition may also form the basis of equivalence due to which these words, as it has been stated above, may be referred to the same subset. The features must be chosen so as to show whether any element we may come across belongs to the given set or not.1 They must also be important, so that the presence of a distinctive feature must allow the prediction of secondary features connected with it. The feature may be constant or variable, or the basis may be formed by a combination of constant and variable features, as in the case of the following group: pool, pond, lake, sea, ocean with its variation for size. Without a basis of similarity no comparison and no opposition are possible. When the basis is not limited to the members of one opposition but comprises other elements of the system, we call the opposition polydimensional. The presence of the same basis or combination of features in several words permits their grouping into a subset of the vocabulary system. We shall therefore use the term lexical group to denote a subset of the vocabulary, all the elements of which possess a particular feature forming the basis of the opposition. Every element of a subset of the vocabulary is also an element of the vocabulary as a whole. It has become customary to denote oppositions by the signs: , ÷ or ::, e. g. The common feature of the members of this particular opposition forming its basis is the adjective stem -skilled-. The distinctive feature is the presence or absence of the prefix un-. This distinctive feature may in other cases also serve as the basis of equivalence so that all adjectives beginning with un- form a subset of English vocabulary (unable, unaccountable, unaffected, unarmed, etc.), forming a correlation: In the opposition man :: boy the distinctive feature is the semantic component of age. In the opposition boy :: lad the distinctive feature is that of stylistic colouring of the second member. The methods and procedures of lexical research such as contextual analysis, componential analysis, distributional analysis, etc. will be briefly outlined in other chapters of the book. _____________________ 1 One must be careful, nevertheless, not to make linguistic categories more rigid and absolute than they really are. There is certainly a degree of “fuzziness” about many types of linguistic sets. 26 Part One THE ENGLISH WORD AS A STRUCTURE Chapter 2 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE WORD AS THE BASIC UNIT OF LANGUAGE § 2.1 THE DEFINITION OF THE WORD Although the borderline between various linguistic units is not always sharp and clear, we shall try to define every new term on its first appearance at once simply and unambiguously, if not always very rigorously. The approximate definition of the term word has already been given in the opening page of the book. The important point to remember about definitions is that they should indicate the most essential characteristic features of the notion expressed by the term under discussion, the features by which this notion is distinguished from other similar notions. For instance, in defining the word one must distinguish it from other linguistic units, such as the phoneme, the morpheme, or the word-group. In contrast with a definition, a description aims at enumerating all the essential features of a notion. To make things easier we shall begin by a preliminary description, illustrating it with some examples. The word may be described as the basic unit of language. Uniting meaning and form, it is composed of one or more morphemes, each consisting of one or more spoken sounds or their written representation. Morphemes as we have already said are also meaningful units but they cannot be used independently, they are always parts of words whereas words can be used as a complete utterance (e. g. Listen!). The combinations of morphemes within words are subject to certain linking conditions. When a derivational affix is added a new word is formed, thus, listen and listener are different words. In fulfilling different grammatical functions words may take functional affixes: listen and listened are different forms of the same word. Different forms of the same word can be also built analytically with the help of auxiliaries. E.g.: The world should listen then as I am listening now (Shelley). When used in sentences together with other words they are syntactically organised. Their freedom of entering into syntactic constructions is limited by many factors, rules and constraints (e. g.: They told me this story but not *They spoke me this story). The definition of every basic notion is a very hard task: the definition of a word is one of the most difficult in linguistics because the 27 simplest word has many different aspects. It has a sound form because it is a certain arrangement of phonemes; it has its morphological structure, being also a certain arrangement of morphemes; when used in actual speech, it may occur in different word forms, different syntactic functions and signal various meanings. Being the central element of any language system, the word is a sort of focus for the problems of phonology, lexicology, syntax, morphology and also for some other sciences that have to deal with language and speech, such as philosophy and psychology, and probably quite a few other branches of knowledge. All attempts to characterise the word are necessarily specific for each domain of science and are therefore considered one-sided by the representatives of all the other domains and criticised for incompleteness. The variants of definitions were so numerous that some authors (A. Rossetti, D.N. Shmelev) collecting them produced works of impressive scope and bulk. A few examples will suffice to show that any definition is conditioned by the aims and interests of its author. Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), one of the great English philosophers, revealed a materialistic approach to the problem of nomination when he wrote that words are not mere sounds but names of matter. Three centuries later the great Russian physiologist I.P. Pavlov (1849-1936) examined the word in connection with his studies of the second signal system, and defined it as a universal signal that can substitute any other signal from the environment in evoking a response in a human organism. One of the latest developments of science and engineering is machine translation. It also deals with words and requires a rigorous definition for them. It runs as follows: a word is a sequence of graphemes which can occur between spaces, or the representation of such a sequence on morphemic level. Within the scope of linguistics the word has been defined syntactically, semantically, phonologically and by combining various approaches. It has been syntactically defined for instance as “the minimum sentence” by H. Sweet and much later by L. Bloomfield as “a minimum free form”. This last definition, although structural in orientation, may be said to be, to a certain degree, equivalent to Sweet’s, as practically it amounts to the same thing: free forms are later defined as “forms which occur as sentences”. E. Sapir takes into consideration the syntactic and semantic aspects when he calls the word “one of the smallest completely satisfying bits of isolated ‘meaning’, into which the sentence resolves itself”. Sapir also points out one more, very important characteristic of the word, its indivisibility: “It cannot be cut into without a disturbance of meaning, one or two other or both of the several parts remaining as a helpless waif on our hands”. The essence of indivisibility will be clear from a comparison of the article a and the prefix a- in a lion and alive. A lion is a word-group because we can separate its elements and insert other words between them: a living lion, a dead lion. Alive is a word: it is indivisible, i.e. structurally impermeable: nothing can be inserted between its elements. The morpheme a- is not free, is not a word. The 28 situation becomes more complicated if we cannot be guided by solid spelling.’ “The Oxford English Dictionary", for instance, does not include the reciprocal pronouns each other and one another under separate headings, although they should certainly be analysed as word-units, not as word-groups since they have become indivisible: we now say with each other and with one another instead of the older forms one with another or each with the other.1 Altogether is one word according to its spelling, but how is one to treat all right, which is rather a similar combination? When discussing the internal cohesion of the word the English linguist John Lyons points out that it should be discussed in terms of two criteria “positional mobility” and “uninterruptability”. To illustrate the first he segments into morphemes the following sentence: the - boy - s - walk - ed - slow - ly - up - the - hill The sentence may be regarded as a sequence of ten morphemes, which occur in a particular order relative to one another. There are several possible changes in this order which yield an acceptable English sentence: slow - ly - the - boy - s - walk - ed - up - the - hill up - the - hill - slow - ly - walk - ed - the - boy - s Yet under all the permutations certain groups of morphemes behave as ‘blocks’ — they occur always together, and in the same order relative to one another. There is no possibility of the sequence s - the - boy, ly - slow, ed - walk. “One of the characteristics of the word is that it tends to be internally stable (in terms of the order of the component morphemes), but positionally mobile (permutable with other words in the same sentence)”.2 A purely semantic treatment will be found in Stephen Ullmann’s explanation: with him connected discourse, if analysed from the semantic point of view, “will fall into a certain number of meaningful segments which are ultimately composed of meaningful units. These meaningful units are called words."3 The semantic-phonological approach may be illustrated by A.H.Gardiner’s definition: “A word is an articulate sound-symbol in its aspect of denoting something which is spoken about."4 The eminent French linguist A. Meillet (1866-1936) combines the semantic, phonological and grammatical criteria and advances a formula which underlies many subsequent definitions, both abroad and in our country, including the one given in the beginning of this book: “A word is defined by the association of a particular meaning with a 1  Sapir E. Language. An Introduction to the Study of Speech. London, 1921, P. 35. Sapir E. Language. An Introduction to the Study of Speech. London, 1921, P. 35.2 Lyons, John. Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics. Cambridge: Univ. Press, 1969. P. 203. 3 Ullmann St. The Principles of Semantics. Glasgow, 1957. P. 30. 4 Gardiner A.H. The Definition of the Word and the Sentence // The British Journal of Psychology. 1922. XII. P. 355 (quoted from: Ullmann St.,Op. cit., P. 51). 29 particular group of sounds capable of a particular grammatical employment."1 This definition does not permit us to distinguish words from phrases because not only child, but a pretty child as well are combinations of a particular group of sounds with a particular meaning capable of a particular grammatical employment. We can, nevertheless, accept this formula with some modifications, adding that a word is the smallest significant unit of a given language capable of functioning alone and characterised by positional mobility within a sentence, morphological uninterruptability and semantic integrity.2 All these criteria are necessary because they permit us to create a basis for the oppositions between the word and the phrase, the word and the phoneme, and the word and the morpheme: their common feature is that they are all units of the language, their difference lies in the fact that the phoneme is not significant, and a morpheme cannot be used as a complete utterance. Another reason for this supplement is the widespread scepticism concerning the subject. It has even become a debatable point whether a word is a linguistic unit and not an arbitrary segment of speech. This opinion is put forth by S. Potter, who writes that “unlike a phoneme or a syllable, a word is not a linguistic unit at all."3 He calls it a conventional and arbitrary segment of utterance, and finally adopts the already mentioned definition of L. Bloomfield. This position is, however, as we have already mentioned, untenable, and in fact S. Potter himself makes ample use of the word as a unit in his linguistic analysis. The weak point of all the above definitions is that they do not establish the relationship between language and thought, which is formulated if we treat the word as a dialectical unity of form and content, in which the form is the spoken or written expression which calls up a specific meaning, whereas the content is the meaning rendering the emotion or the concept in the mind of the speaker which he intends to convey to his listener. Summing up our review of different definitions, we come to the conclusion that they are bound to be strongly dependent upon the line of approach, the aim the scholar has in view. For a comprehensive word theory, therefore, a description seems more appropriate than a definition. The problem of creating a word theory based upon the materialistic understanding of the relationship between word and thought on the one hand, and language and society, on the other, has been one of the most discussed for many years. The efforts of many eminent scholars such as V.V. Vinogradov, A. I. Smirnitsky, O.S. Akhmanova, M.D. Stepanova, A.A. Ufimtseva — to name but a few, resulted in throwing light _____________________ 1 Meillet A. Linguistique historique et linguistique generate. Paris, 1926. Vol. I. P. 30. 2 It might be objected that such words as articles, conjunctions and a few other words never occur as sentences, but they are not numerous and could be collected into a list of exceptions. 3 See: Potter S. Modern Linguistics. London, 1957. P. 78. 30 on this problem and achieved a clear presentation of the word as a basic unit of the language. The main points may now be summarised. The word is the fundamental unit of language. It is a dialectical unity of form and content. Its content or meaning is not identical to notion, but it may reflect human notions, and in this sense may be considered as the form of their existence. Concepts fixed in the meaning of words are formed as generalised and approximately correct reflections of reality, therefore in signifying them words reflect reality in their content. The acoustic aspect of the word serves to name objects of reality, not to reflect them. In this sense the word may be regarded as a sign. This sign, however, is not arbitrary but motivated by the whole process of its development. That is to say, when a word first comes into existence it is built out of the elements already available in the language and according to the existing patterns. § 2.2 SEMANTIC TRIANGLE The question that now confronts us is this: what is the relation of words to the world of things, events and relations outside of language to which they refer? How is the word connected with its referent? The account of meaning given by Ferdinand de Saussure implies the definition of a word as a linguistic sign. He calls it ‘signifiant’ (signifier) and what it refers to — ‘signifie’ (that which is signified). By the latter term he understands not the phenomena of the real world but the ‘concept’ in the speaker’s and listener’s mind. The situation may be represented by a triangle (see Fig. 1).  Here, according to F. de Saussure, only the relationship shown by a solid line concerns linguistics and the sign is not a unity of form and meaning as we understand it now, but only sound form. Originally this triangular scheme was suggested by the German mathematician and philosopher Gottlieb Frege (1848-1925). Well-known English scholars C.K. Ogden and I.A. Richards adopted this three-cornered pattern with considerable modifications. With them a sign is a two-facet unit comprising form (phonetical and orthographic), regarded as a linguistic symbol, and reference which is more _____________________ 1 A concept is an idea of some object formed by mentally reflecting and combining its essential characteristics. 31 linguistic than just a concept. This approach may be called referential because it implies that linguistic meaning is connected with the referent. It is graphically shown by there being only one dotted line. A solid line between reference and referent shows that the relationship between them is linguistically relevant, that the nature of what is named influences the meaning. This connection should not be taken too literally, it does not mean that the sound form has to have any similarity with the meaning or the object itself. The connection is conventional.  Several generations of writers, following C.K. Ogden and I.A. Richards, have in their turn taken up and modified this diagram. It is known under several names: the semantic triangle, triangle of signification, Frege semiotic triangle, Ogden and Richards basic triangle or simply basic triangle. We reproduce it for the third time to illustrate how it can show the main features of the referential approach in its present form. All the lines are now solid, implying that it is not only the form of the linguistic sign but also its meaning and what it refers to that are relevant for linguistics. The scheme is given as it is applied to the naming of cats.  The scheme is still over-simplified and several things are left out. It is very important, for instance, to remember that the word is represented by the left-hand side of the diagram — it is a sign comprising the name and the meaning, and these invariably evoke one another. So we have to assume that the word takes two apexes of the triangle and the line connecting them. In some versions of the triangle it is not the meaning but the concept that is placed in the apex. This reflects the approach to the problem as formulated by medieval grammarians; it remained traditional for many centuries. 32 We shall deal with the difference between concept and meaning in § 3.2. In the modification of the triangle given here we have to understand that the referent belongs to extra-linguistic reality, it is reflected in our mind in several stages (not shown on the diagram): first it is perceived, then many perceptions are generalised into a concept, which in its turn is reflected in the meaning with certain linguistic constraints conditioned by paradigmatic influence within the vocabulary. When it is the concept that is put into the apex, then the meaning cannot be identified with any of the three points of the triangle.1 The diagram represents the simplest possible case of reference because the word here is supposed to have only one meaning and one form of fixation. Simplification, is, however, inherent to all models and the popularity of the semantic triangle proves how many authors find it helpful in showing the essence of the referential approach. |