Законодательная власть и правоохранительная деятельность в Великобритании и США учебное пособие Уровень В1 Составитель

Скачать 3.57 Mb. Скачать 3.57 Mb.

|

|

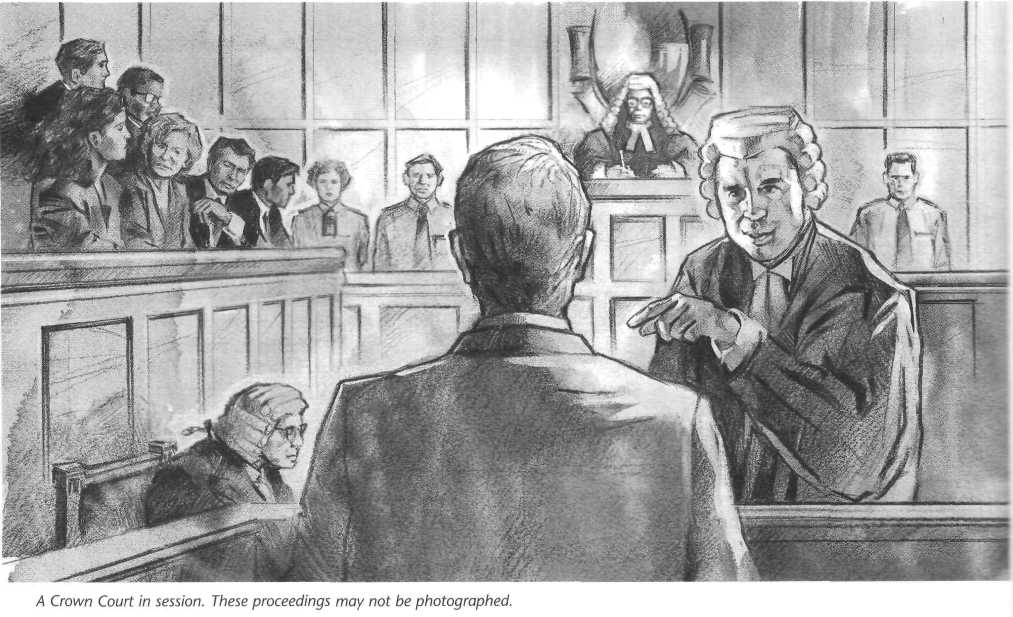

2. Jigsaw Reading Decide which text you want to read and divide into two groups. Group A Read about the court system of the USA. Group B Read about the court system of the UK. Work with other students in your group. Check if your answers to the questions above were correct and fill out the third column of the chart about your text. Find a partner from the other group and swap information about the two court systems following the questions above. Fill out the third column in the chart about your partner’s text. Text A The Court System of the USA (1) The Constitution, written in 1787, established a separate judicial branch of government which operates independently alongside the executive and legislative branches. Within the judicial branch, authority is divided between state and federal (national) courts. At the head of the judicial branch is the Supreme Court, the final interpreter of the Constitution. (2) The Constitution recognizes that the states have certain rights and authorities beyond the power of the federal government. States have the power to establish their own systems of criminal and civil laws, with the result that each state has its own laws, prisons, police force, and state court. Within each state, there are also county and city courts. Generally, state laws are quite similar, but in some areas there is great diversity. The minimum age for marriage and the sentences for murder vary from state to state. The minimum legal age for the purchase of alcohol is 21 in most states. (3) The separate system of federal courts, which operates alongside the state courts, handles cases which arise under the U.S. Constitution or under any law or treaty, as well as any controversy to which the federal government is itself a party. Federal courts also hear disputes involving governments or citizens of different states. (4) All federal judges are appointed for life. A case which falls within federal jurisdiction is heard first before a federal district judge. An appeal may be made to the Circuit Court of Appeals, and, possibly, in the last resort, to the highest court in the land: the U.S. Supreme Court. (5) The Supreme Court hears cases in which someone claims that a lower court ruling is unjust or in which someone claims that Constitutional law has been violated. Its decisions are final and become legally binding. Although the Supreme Court does not have the power to make laws, it does have the power to examine actions of the legislative, executive, and administrative institutions of the government and decide whether they are constitutional. It is in this function that the Supreme Court has the potential to influence decisively the political, social, and economic life of the country. (6) In the past, Supreme Court rulings have given new protection and freedom to blacks and other minorities. The Supreme Court has nullified certain laws of Congress and has even declared actions of American presidents unconstitutional. The U.S. government is so designed that, ideally, the authority of the judicial branch is independent from the other branches of government. Each of the nine Supreme Court justices (judges) is appointed by the president and examined by the Senate to determine whether he or she is qualified. Once approved, a justice remains on the Supreme Court for life. The Supreme Court justices have no obligation to follow the political policies of the president or Congress. Their sole obligation is to uphold the laws of the Constitution. (7) Nevertheless, politics play a role in a president's selection of a Supreme Court justice. On average, a president can expect to appoint two new Supreme Court justices during one term of office. Presidents are likely to appoint justices whose views are similar to their own, with the hope that they can extend some of their power through the judicial branch. /Adapted from America in Close-up. Eckhard Fielder, Reimer Jansen, Mil Norman-Risch/ Text B The Court System of the UK (1) The initial decision to bring a criminal charge normally lies with the police, but since 1986 a Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) has examined the evidence on which the police have charged a suspect to decide whether the case should go to court. Generally it brings to court only those cases which it believes will be successful, a measure to avoid the expense and waste of time in bringing unsound cases to court. However, the collapse of several major cases and the failure to prosecute in other cases have both led to strong criticism of the CPS. (2) There are two main types of court for criminal cases: Magistrates' Courts (or 'courts of first instance'), which deal with about 95 per cent of criminal cases, and Crown Courts for more serious offences. All criminal cases above the level of Magistrates' Courts are held before a jury. Civil law covers matters related to family, property, contracts and torts (wrongful acts suffered by one person at the hands of another). These are usually dealt with in County Courts, but specialised work is concentrated in certain designated courts. The High Court deals with more complicated cases and is divided into three: the Family Division, which deals with family law, divorce and adoption; Chancery, which deals with corporate and personal insolvency, interpretation of trusts and wills; and the Queen's Bench, which deals with contract and tort cases, maritime and commercial law.  (3) There are about 400 Magistrates' Courts in England and Wales, served by approximately 30,000 unpaid or 'lay' magistrates or Justices of the Peace (JPs), who have been dealing with minor crimes for over 600 years. JPs are ordinary citizens chosen from the community. They are appointed by the Lord Chancellor, but on the recommendation of advisory committees of local people. These committees sometimes advertise for applicants. They are required not only to interview, but to make their selection not only on suitability but also ensuring that composition of 'the Bench' broadly reflects the community it serves. In recent years women and members of ethnic minority communities have been recruited to moderate the once overwhelmingly white, male, character of the JP cadre. (3) There are about 400 Magistrates' Courts in England and Wales, served by approximately 30,000 unpaid or 'lay' magistrates or Justices of the Peace (JPs), who have been dealing with minor crimes for over 600 years. JPs are ordinary citizens chosen from the community. They are appointed by the Lord Chancellor, but on the recommendation of advisory committees of local people. These committees sometimes advertise for applicants. They are required not only to interview, but to make their selection not only on suitability but also ensuring that composition of 'the Bench' broadly reflects the community it serves. In recent years women and members of ethnic minority communities have been recruited to moderate the once overwhelmingly white, male, character of the JP cadre.(4) A court normally consists of three lay magistrates who are advised on points of law by a legally qualified clerk. They may not impose a sentence of more than six months imprisonment or a fine of more than £5,000, and may refer cases requiring a heavier penalty to the Crown Court. (5) A Crown Court is presided over by a judge, but the verdict is reached by a jury of 12 citizens, randomly selected from the local electoral rolls. The judge must make sure that the trial is properly conducted, that the 'counsels' (barristers) for the prosecution and defence comply with the rules regarding the evidence that they produce and the examination of witnesses, and that the jury are helped to reach their decision by the judge's summary of the evidence in a way which indicates the relevant points of law and the critical issues on which they must decide in order to reach a verdict. Underlying the whole process lies the assumption that the person charged with an offence is presumed to be innocent unless the prosecution can prove guilt 'beyond all reasonable doubt'. Recent complex cases involving financial fraud have opened a debate as to whether certain kinds of case should be tried by a panel of experts capable of understanding fully what a case involves.

/Adapted from Britain in Close-up. David McDowall/ 3. Focus on Language 1. Building vocabulary: Using Context Clues

Find words in the text that match the definitions below.

Compare your answers in a small group. Discuss which clues helped you. 2. In the texts such words as ‘case’ and ‘sentence’ were used. Work with your English-English dictionary and check what some of the most useful collocations are. 4. Speaking 4 1. Make the mindmaps about the court systems of the USA and the UK. Work in pairs and describe the two systems. 2. Compare either of the courts with that of your country. Reading 4 The legal profession 1. Pre-reading task Using the SQR3 system

In this pre-reading activity we will look at the first three steps in the SQR3 system: survey, question and read. 1 Survey

2 Question

3 Read

There are two distinct kinds of lawyer in Britain. One of these is a solicitor. Everybody who needs a lawyer has to go to one of these. They handle most legal matters for their clients, including the drawing up of documents (such as wills, divorce papers and contracts), communicating with other parties, and presenting their clients' cases in magistrates' courts. However, only since 1994 have solicitors been allowed to present cases in higher courts. If the trial is to be heard in one of these, the solicitor normally hires the services of the other kind of lawyer - a barrister. The only function of barristers is to present cases in court. There are two distinct kinds of lawyer in Britain. One of these is a solicitor. Everybody who needs a lawyer has to go to one of these. They handle most legal matters for their clients, including the drawing up of documents (such as wills, divorce papers and contracts), communicating with other parties, and presenting their clients' cases in magistrates' courts. However, only since 1994 have solicitors been allowed to present cases in higher courts. If the trial is to be heard in one of these, the solicitor normally hires the services of the other kind of lawyer - a barrister. The only function of barristers is to present cases in court.The training of the two kinds of lawyer is very different. All solicitors have to pass the Law Society exam. They study for this exam while 'articled' to established firms of solicitors where they do much of the everyday junior work until they are qualified. Barristers have to attend one of the four Inns of Court in London. These ancient institutions are modelled somewhat on Oxbridge colleges. For example, although there are some lectures, the only attendance requirement is to eat dinner there on a certain number of evenings each term. After four years, the trainee barristers then sit exams. If they pass, they are 'called to the bar' and are recognized as barristers. However, they are still not allowed to present a case in a crown court. They can only do this after several more years of association with a senior barrister, after which the most able of them apply to 'take silk'. Those whose applications are accepted can put the letters QC (Queen's Counsel) after their names. Neither kind of lawyer needs a university qualification. The vast majority of barristers and most solicitors do in fact go to university, but they do not necessarily study law there. This arrangement is typically British. The different styles of training reflect the different worlds that the two kinds of lawyer live in, and also the different skills that they develop. Solicitors have to deal with the realities of the everyday world and its problems. Most of their work is done away from the courts. They often become experts in the details of particular areas of the law. Barristers, on the other hand, live a more rarefied existence. For one thing, they tend to come from the upper strata of society. Furthermore, their protection from everyday realities is increased by certain legal rules. For example, they are not supposed to talk to any of their clients, or to their client's witnesses, except in the presence of the solicitor who has hired them. They are experts on general principles of the law rather than on details, and they acquire the special skill of eloquence in public speaking. When they present a case in court, they, like judges, put on the archaic gown and wig which, it is supposed, emphasize the impersonal majesty of the law. It is exclusively from the ranks of barristers that judges are appointed. Once they have been appointed, it is almost impossible for them to be dismissed. The only way that this can be done is by a resolution of both Houses of Parliament, and this is something that has never happened. Moreover, their retiring age is later than in most other occupations. They also get very high salaries. These things are considered necessary in order to ensure their independence from interference, by the state or any other party. However, the result of their background and their absolute security in their jobs is that, although they are often people of great learning and intelligence, some judges appear to have difficulty understanding the problems and circumstances of ordinary people, and to be out of step with general public opinion. The judgements and opinions that they give in court sometimes make the headlines because they are so spectacularly out of date. (The inability of some of them to comprehend the meaning of racial equality is one example. A senior Old Bailey judge in the 1980s once referred to black people as 'nig-nogs' and to some Asians involved in a case as 'murderous Sikhs'.) /Adapted from Britain. James O’Driscoll/ After you read 1. USING THE SQR3 SYSTEM The SQR3 system continues after reading a text. The fourth step is to recite, or say aloud from memory, and the last step is to review. 1 Recite When you recite, you say aloud from memory what you have read about. You can do this while reading, stopping after each paragraph and asking yourself: Now what did I just read? Do I understand the main ideas? Did the text answer my question? Choose a paragraph from the text. Re-read it and then tell a partner what your paragraph was about. Listen to your partner tell you about a different paragraph. 2 Review

2. Language focus a. Explain or paraphrase the collocations in bold. 1. They study for this exam while 'articled' to established firms of solicitors… 2. If they pass, they are 'called to the bar' and are recognized as barristers. 3. They can only do this after several more years of association with a senior barrister, after which the most able of them apply to 'take silk'. | ||||||||||